Become a Valuer

Lesson 5: Create Values (1 of 3)

Many people’s lives are ruled by what author John Demartini calls “social idealisms”: “socially acceptable ways of thinking and behaving.” These are things we “should” do, or “have to” do, or are “supposed to” do, but don’t genuinely want to do. They aren’t chosen values but unchosen duties.

To achieve happiness, Demartini argues, we need to be guided by our highest values. Your highest values aren’t something imposed on you by an external authority. They are “the very essence of you: what you’re drawn to, what you inevitably seek out, what you live for.”

In Demartini’s account, you discover your highest values, not by sitting down and envisioning a life that you think you would be passionate about ex nihilo, but by examining your actual life to discover what you genuinely value in practice. To identify your highest values, Demartini recommends asking thirteen questions, and supplying three examples for each:

How do you fill your personal and professional space?

How do you spend your time?

How do you spend your energy?

How do you spend your money?

Where do you have the most order and organization?

Where are you most reliable, disciplined, and focused?

What do you think about, and what is your innermost dominant thoughts?

What do you visualize and realize?

What is your internal dialogue?

What do you talk about in social settings?

What inspires you?

What are the most consistent long-term goals that you have set?

What do you love to learn about the most?

According to Demartini, these questions will help elicit the top values in your life—things you already value that you can now purposefully choose to build your life around.

I regard Demartini’s advice as extremely useful for helping you discard pointless duties and unearthing what you truly value. But it’s not sufficient because even if you throw away external “shoulds,” it’s all too easy to adopt values that are inconsistent and bad for your life. In philosophical terms, Demartini replaces intrinsicism (duty) with subjectivism (feelings). Demartini believes that moral codes as such are at odds with personal values, and that the only test that matters is whether you already value something. But the truth is that a rational, pro-life, pro-self moral code is the only way to choose and achieve personal values that lead to happiness.

Pursuing your happiness means focusing on the achievement of pro-life values, and the achievement of pro-life values means practicing the virtue of rationality—it means being a thinker. A thinker goes after what he wants, but he doesn’t decide what to want lightly. When selecting his values, he applies three crucial tests over and above answering the kinds of questions Demartini would have us ask: the reality test, the cost test, and the integration test.

(1) The reality test. The thinker only pursues goals that are achievable. This doesn’t mean easy to achieve. The thinker is ambitious. He wants the best possible. But that also means he wants the best possible.

In part that means possible to man; he has no sympathy for those who yearn for a life free from effort, struggle, failure, or death. In part that means possible to him. As a child I wanted to be a professional baseball player. But after it became clear I didn’t have the speed, strength, eyesight, or hand-eye coordination to give me even a fighting chance, playing pro ball no longer represented a value to me.

The reality test involves more than working to achieve goals that are realistic—it means valuing values. It means that you don’t chase after whatever you happen to desire, but you’re interested in whether your desires are genuinely good for you—whether they work to keep you in reality.

Human beings are capable of pursuing goals that work to our detriment. We can pursue relationships that leave us drained and diminished. We can consume substances that weaken our bodies and subvert our minds. If we do not examine our desires to ask ourselves why we want what we want, we can pursue seemingly legitimate values in self-destructive ways: we can want a job, not because we love it, but because it will impress people. We can want a lover, not because we’re in love, but because we want others to envy us. Our actions can lead us, not to the achievement of life-promoting positives, but to a hollow collection of trophies displayed in the entryway of an empty house.

Every value is both an end and a means to some further value. The thinker examines every value to see the ultimate ends it is aimed at fulfilling. Are they pro-life—or not? He works to see the full ramifications of what he’s after on his life—and will not tolerate anything that will weaken him or subvert his life. Or, to put it positively, he sees every value in its full light, and only endorses those values that brighten his life and his ability to deal with reality.

(2) The cost test. If a value is achievable and pro-life, the thinker identifies the means necessary to achieve it. He never embraces a value without assuming responsibility for the effort required to achieve it. If he’s considering whether to become an entrepreneur, he will want to know: what’s required to become an entrepreneur? And he will ask himself: is that a price I’m willing to pay? For great values, he’s willing to pay a great price, embracing the fact that every value requires effort. But if he isn’t willing to pay the price, then he will not adopt the value.

(3) The integration test. We don’t pursue values in isolation. At minimum, time spent in the pursuit of one goal means time taken away from other goals. Happiness is a state of non-contradictory joy, where the achievement of one value doesn’t entail the frustration of another. The thinker works to bring his values into harmony. If a potential value cannot be integrated with his other values, then he will not adopt it.

Years ago I saw the documentary Still Bill, about the musician Bill Withers, who quit music at the peak of his fame. The most striking aspect of the documentary was Withers’ clear, independent sense of what he was about. He had a vision of what he wanted from life, and fortune and fame meant nothing to him if it wasn’t consistent with that vision.

That is what it what it looks like to be a thinker. It’s not simply having a few values that you go after; it’s building a life. It’s conceiving of what you want your days to add up to, then saying “yes” to everything that moves you toward that vision and saying “no” to anything that doesn’t.

Life and happiness are not the result of achieving a single value, but a code of values—a systematic constellation of values that fit together into a self-sustaining whole. Not everyone has a code of values. Not everyone knows what they’re about. The values they do have are chiefly held in emotional form, intermingled with duties and compulsions and fears. If they do have clear, crisp values, these are often compartmentalized into the sphere of life where they feel most in control (usually work). But their pursuits don’t add up to anything—or don’t add up to anything consistent.

In her notes for an early novel she planned but never wrote, Rand describes this mentality:

Most people lack [the capacity for] reverence and “taking things seriously.” They do not hold anything to be very serious or profound. There is nothing that is sacred or immensely important to them. There is nothing—no idea, object, work, or person—that can inspire them with a profound, intense, and all-absorbing passion that reaches to the roots of their souls. They do not know how to value or desire. They cannot give themselves entirely to anything. There is nothing absolute about them. They take all things lightly, easily, pleasantly—almost indifferently, in that they can have it or not, they do not claim it as their absolute necessity.

You cannot be all-in on your values if they aren’t clearly defined and integrated into a consistent whole. Instead, your desires become muted, contradictory, and all-too-often self-defeating. The lethargy and bland conventionality and ostentatious shallowness and unhappiness you encounter in most people finds its roots here: it is an intellectual failure. They have not made the commitment to being goal-directed, have not thought about what they want, and so they “do not know how to value or desire.”

The purpose of this lesson is to teach you how to value. It’s to teach you how to achieve a truly purpose-driven life—a life rich in meaning, passion, and joy. A life that you love.

Create your value hierarchy

The basic challenge of integrating your values is arranging your life so that all of your crucial needs get met. Even if your values are rational and fit together in principle, it is all too easy to neglect crucial values in practice. You allow work to rob you of human connection or you allow your family demands to trump self-care. To pursue a life is to treat all of your vital needs as sacred, and, to the extent you can, structure your life so that you can tend to all of your major values.

What that means in practice is establishing a value hierarchy. Rand explains:

A moral code is a set of abstract principles; to practice it, an individual must translate it into the appropriate concretes—he must choose the particular goals and values which he is to pursue. This requires that he define his particular hierarchy of values, in the order of their importance, and that he act accordingly.

A hierarchy of values allows you to make decisions about how to live your day-to-day life because it identifies what’s most important to you—and it allows you to see how smaller, even trivial decisions relate to your highest, most long-term goals. For example, a fulfilling marriage is not the result of a single grand, sweeping gesture. It is the result of countless small actions: actively listening while your partner tells you about his day, a meaningful compliment as she leaves for work, sharing a secret, playing a game of Scrabble, a thoughtful birthday gift. These concrete activities are how you create a fulfilling marriage, and they are what a fulfilling marriage consists of. Someone who claims to love his partner, and yet rushes out the door in the morning and holes up in a man cave at night, who cannot make time for his partner, who cannot make it through a shared meal without checking his work email, does not actually value his marriage, whatever he might claim.

To honor your values, you have to identify their relative importance in your life and then translate that into specific concrete actions, never sacrificing a higher value to a lower value.

How exactly do you form a hierarchy of values? A hierarchy of values is, in essence, a time hierarchy. To value something is to spend time on that pursuit. This doesn’t always mean that your most important values get the most time, but they do get first claim on your time. I might, for example, spend more time watching baseball each week than having sex, but sex is a higher value because it gets prioritized over watching the Phillies. In forming a value hierarchy, the question I’m trying to answer: what are my priorities? What has first claim on my time, energy, and resources?

To form a time hierarchy, you can’t simply make a list of all the things you value and try to rank them from 1 to 10,000. How would you compare going to the gym to listening to Bach to a new pair of shoes? At that level of analysis, your values are incommensurable. Instead, you need to start by identifying broad categories of values that capture all the things you have to achieve to live a secure, fulfilling life. For example, your list might consist of:

Creation

Connection

Recreation

Self-maintenance

These are the areas in which you have to divide up your time. The fact that creation is more important to you than connection doesn’t mean you want to spend all your time creating. Since you have to meet all your important needs to achieve happiness, what it means is that your creative work has the primary claim on your time.

Within a given category, then, you can make a ranked list of concrete values. Take the value of connection. You might think: I’m going to devote most of my afternoons this week to connecting with the people I value. And my hierarchy of companions might be: my romantic partner, then my kids, then my best friend, then my other friends. So most of my time is going to go to my girlfriend and kids. Then I’m going to spend Saturday night with my best friend and hop on a Zoom call with an old college buddy on Sunday.

In most value categories, you’ll want to identify subcategories before creating ranked lists of concrete values. For example, you might break recreation down into exercise, inspiration, learning, excitement, pleasure—and then make ranked lists of specific values. Once you’ve gotten your hour of exercise for the day, for example, you’re not going to use any remaining recreation time to go for a hike—you might watch a documentary or listen to Swan Lake.

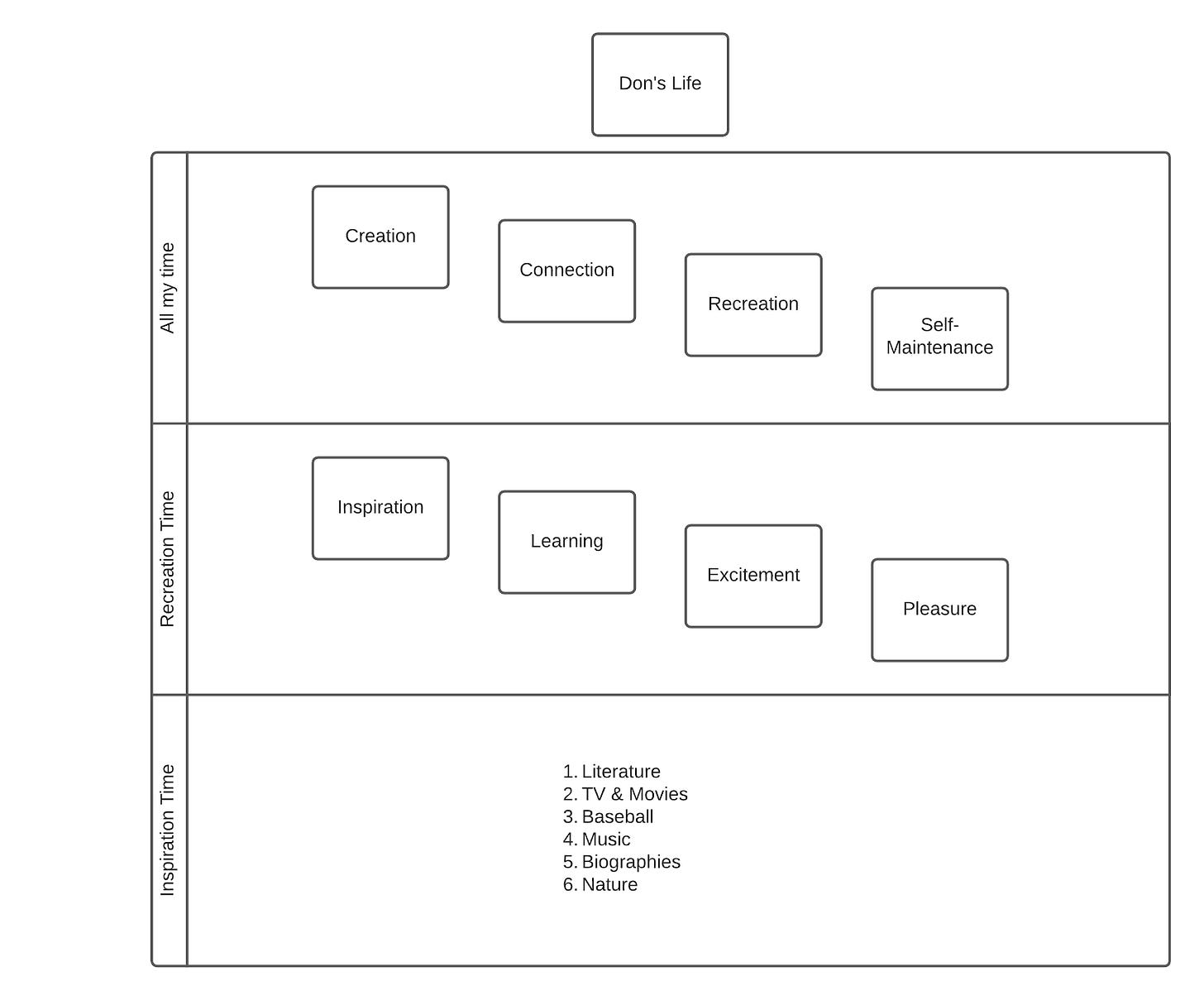

Figure 1 shows a rough sketch of how you might work out part of your value hierarchy.

Your value hierarchy doesn’t have to be this formalized and detailed. What’s crucial is that you have a general ranking of all your most important values and that when conflicts arise or when you notice some of your needs going unmet, you can step back and clarify for yourself what matters most.

You can think of this as a top-down approach to your value hierarchy. But there’s also what you can call a bottom-up approach. When you’re contemplating something you want to do or feel you have to do, you might not have a clear sense of where it belongs in your hierarchy of values.

Here it’s crucial to remember that all values stand in a means/ends relationship to other values. Right now on my to-do list I have “set up a Health Savings Account.” To see where this fits in my value hierarchy, I need to ask, “Why is this a value? What will I gain by doing this or what will I lose by not doing this?” In this case, an HSA will save me money by allowing me to pay my healthcare bills with pre-tax income. That means it belongs under “financial health,” which is near the top of my “self-maintenance” hierarchy. When I sit down to focus on my financial health, which I typically do at the end of each month, I’m going to see that making the time to open an HSA is a high-leverage activity: it will take about an hour or two to set up, and yet could save me hundreds or thousands of dollars a year. That’s going to take precedence over a lot of other money-saving activities.

One of the benefits of formulating a hierarchy of values and seeing how every activity fits within your hierarchy is that the world becomes value rich. The smallest value takes on an elevated level of meaning and importance because you see its role in serving your highest values.

For example, I spend most of my life in my home office. By seeing my home office as intimately connected to the career that I love, it becomes more than a place to sit down and type. I can see it as a sacred environment where I do what I love. And that encourages me to create the kind of environment that helps me do my work and enjoy my work. In front of me, there’s a window which I’ve fitted with a scarlet curtain (my favorite color) and next to it a portrait of Ayn Rand (my favorite author). On my desk is a soothing water fountain with tea lights. At my feet is a yellow carpet that makes me feel as if I’m stepping into a bright, energized, but relaxed universe every time I enter my office. I’m surrounded by books that make me feel as if I’m living among history’s great minds.

That is what it means to fill your life with values. You can turn every area of your life into a slice of personal heaven. You can turn your home into your ideal universe. You can make your wardrobe an expression of soul. You can fill your kitchen with your favorite food and choose a car that serves and expresses your lifestyle. You can—and you should—rearrange the world so that it comes closer to your vision of the ideal world. You can create a stylized universe of your own making—a universe that elevates you, heightens the mundane, and accentuates the exceptional.

When you make your life value rich, something else happens as well. Most of your highest values are long range and abstract. But when you come to see the means to those values as themselves being values, you have the continuing experience of successfully achieving values. My most important career value right now is to write this book. But I cannot sit down and “write this book.” What I can do is set as my value spending three hours a day writing. Each day that I’ve invested those three hours is an achievement of one of my values. Contrast that with people whose life is a series of obnoxious duties performed in the hopes that one day far in the future they’ll get what they want. You can get what you want today—by seeing what you can achieve today as serving your long-term vision.

The virtue of productiveness

I’ve left out one crucial ingredient of a value hierarchy: the purpose at its center. Without a central purpose, you cannot formulate or follow a hierarchy of values. According to Rand:

A central purpose serves to integrate all the other concerns of a man’s life. It establishes the hierarchy, the relative importance, of his values, it saves him from pointless inner conflicts, it permits him to enjoy life on a wide scale and to carry that enjoyment into any area open to his mind; whereas a man without a purpose is lost in chaos. He does not know what his values are. He does not know how to judge. He cannot tell what is or is not important to him, and, therefore, he drifts helplessly at the mercy of any chance stimulus or any whim of the moment. He can enjoy nothing. He spends his life searching for some value which he will never find.

Only one kind of purpose is fit to be a central purpose: a productive career.

Our need to work is often blamed on capitalism. Absent capitalism’s delusions, we would exist in harmony with nature, spending a few hours growing fruit and the rest of the time relaxing with friends and family and playing folk music or whatever. That part is never too clear. What is clear is that, according to capitalism’s critics, the time and attention we give to our careers is a disease motivated by an unquenchable desire to consume. “We buy things we don’t need with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like,” Chuck Palahniuk tells us in Fight Club.

But it’s the critics of work who are delusional. Non-capitalist societies are idealized only by people who don’t have to live in them. It’s capitalism and the technological innovation it generates that liberated us from endless grueling hours in the sun, the countless dangers of farming, the primitive ignorance of people who had not built universities and the printing press, the nasty, brutish, short lives that people led in prior ages. Capitalism doesn’t delude us into working—it liberates us to do the kind of work we want, the way we want to do it, and to live better than kings did a few centuries ago. Capitalism increases the material and spiritual rewards of work. But the need to work? That’s built into us.

Biologically, we need material values in order to survive—productive work is how we create them. Human beings can’t live “in harmony with nature” the way animals do. Animals are programmed to consume the resources in their environmental niche (with many members of a species dying in the struggle for a fixed supply of resources). Human beings lack that kind of programming. Venture out into to the wilderness without the tools of modern civilization (or just read Into the Wild) and you’ll quickly find that living “in harmony with nature” really means dying in harmony with nature.

We don’t consume ready-made material values—we create them through productive work. We look around our environment, figure out how to make the raw material of nature useful to us, then exert the effort to bring new resources and values into existence. We don’t just pluck fruit off wild bushes—we plant crops. We don’t just hunt animals—we breed them. We don’t live in caves—we build houses. We don’t scratch words into the dirt—we create the printing press and the Internet. We use reason to project a better future and use reason to bring that future into existence. This is why there’s no need for the “less fit” members of our species to die off: we don’t fight for a fixed sum of resources—we create abundance.

Productive work isn’t just one activity human life requires, but the central activity. Life is a process of self-sustaining action. Most human activities—even important ones—consist of consuming values. Visiting the doctor, pursuing a hobby, traveling with friends, taking your partner on a date all involve expending resources. A self-sustaining life requires the continual replenishing of our resources, and only productive work can accomplish that. As a result, when we formulate our hierarchy of values—when we decide how we will apportion our time among the various things we care about—productive work has to have first claim on our time and energy. Our central purpose must be a productive purpose. Productive creation is what makes a human life self-sustaining. It’s how we bring new values into existence.

The insignia of productive work’s unique place in life is the pleasure we take in the process of creating values. Famed educator Maria Montessori observed that this joy in work can be seen even in children. Children, she notes:

don’t consider what they do to be play—it is their work. . . . If the mother is making bread, the child is given a little flour and water too, so that he can also make bread; if the mother is sweeping a room, the child has a little brush and helps her. They wash clothes alongside the mother. The child is very, very happy.

But the pleasure of work depends in large measure on the extent to which it uses the full resources of our mind. For an adult, baking bread and washing clothes can be drudgery. We need work that challenges us, that requires us to learn, grow, think creatively. But if we do find such work, then, like children, it can become an all-consuming source of passion and pride.

This is the virtue of productiveness. The essence of a moral life is using your intelligence to create values. This sets your central purpose, and allows you to build a life, rather than to drift through a series of disconnected days. As Rand puts it:

Productive work is the road of man’s unlimited achievement and calls upon the highest attributes of his character: his creative ability, his ambitiousness, his self-assertiveness, his refusal to bear uncontested disasters, his dedication to the goal of reshaping the earth in the image of his values. “Productive work” does not mean the unfocused performance of the motions of some job. It means the consciously chosen pursuit of a productive career, in any line of rational endeavor, great or modest, on any level of ability. It is not the degree of a man’s ability nor the scale of his work that is ethically relevant here, but the fullest and most purposeful use of his mind.

The virtue of productiveness tells us that we need to produce in order to live—and that if we want to enjoy life, our work must be a source, not only of wealth, but of joy. As the hero of Rand’s novel The Fountainhead says, “I have, let’s say, sixty years to live. Most of that time will be spent working. I’ve chosen the work I want to do. If I find no joy in it, then I’m only condemning myself to sixty years of torture.”

Too often we settle for a job that pays the bills, a job that makes us lust for Fridays and fear Mondays. That is ghastly. We should not tolerate torture. We should not tolerate one ounce of needless suffering. If our goal is to live and enjoy life, then we need to create for ourselves a career that we love. But how do we do that?

Great stuff Don. So much clarity.