Solving History’s Greatest Ethical Dilemma

How do you justify an ultimate value?

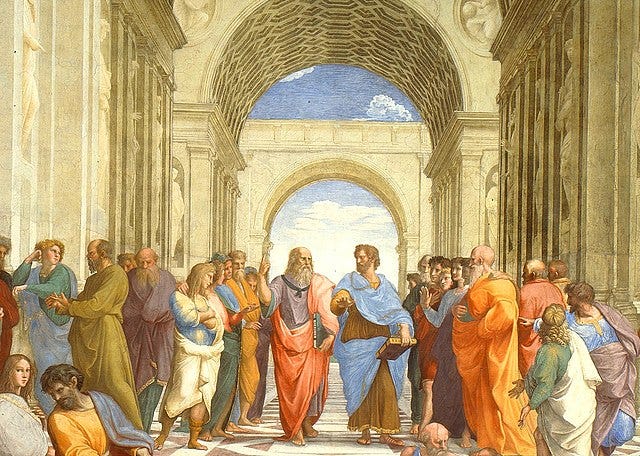

For more than 2,000 years, ethical thinkers have struggled with a riddle. How do you justify a moral theory’s ultimate value?

An ultimate value is what an ethical theory identifies as the highest good—and the standard for assessing other things as good or bad. Is it money? Honor? Pleasure? The greatest happiness for the greatest number? Doing God’s will?

The problem comes once you’ve asserted something as an ultimate value: if it is the standard of what’s good, what makes it good? It makes sense to say that food, sex, and roller coasters are good because they produce pleasure. But why make pleasure the standard? Why not the greatest happiness for the greatest number? It seems like you need to appeal to something beyond pleasure to say that it’s good. And, yet, if there were something beyond pleasure you could appeal to, then pleasure wouldn’t be ultimate.

Thinkers have responded to this riddle in two main ways. One way is to say that their ultimate value is intrinsically valuable. But that’s not really different from saying, “I can’t prove this is valuable, but I just feel like it is.” The other way is to look at all these conflicting claims about intrinsic values and to conclude that ethics is inherently arbitrary.

But there’s something wrong with this entire approach to ethics. We can’t start by asking which ultimate value we should pursue. Following Ayn Rand, we need to ask a more basic question: what are values?

Once we’ve answered that, it turns out we can settle the issue of what is the right ultimate value without arbitrarily appealing to some “intrinsic” value—and without conceding that ethics is arbitrary.

Values = goals + stakes

To make sense of something as a value, we need to see an entity acting to gain (or keep) it. A value is an object of goal-directed action. Take away goal-directed action, and it simply doesn’t make sense to talk about values. There are no values on Venus.

But action by itself isn’t enough. To make sense of something as a value, we also need to see that the entity acting to gain it is affected by the outcome. That it has skin in the game. That it’s taking an action with stakes.

To drive this point home, Rand has us try to imagine an immortal, indestructible robot, “an entity which moves and acts, but which cannot be affected by anything, which cannot be changed in any respect, which cannot be damaged, injured or destroyed. Such an entity would not be able to have any values.” Why not? Because “it would have nothing to gain or to lose; it could not regard anything as for or against it, as serving or threatening its welfare, as fulfilling or frustrating its interests. It could have no interests and no goals.”

So where do we see goal-directed action with stakes? We see it with things that aren’t immortal or indestructible. With things that can be damaged, injured, and destroyed. With living organisms.

Life is goal-directed action with stakes

There is a radical difference between living organisms and everything else in nature: living organisms pursue goals. And not just any goals. Across the countless activities that make up a living being’s way of life, the central concern that explains its actions is: the struggle for survival.

Living organisms act to achieve goals that sustain their lives. If they don’t—or if they fail to achieve their goals—they slow down, weaken, malfunction, suffer, and die. If values require goal-directed action with stakes, then life just is goal-directed action with stakes.

There is nothing mystical or arbitrary about values and evaluative concepts like “good,” “bad,” “right,” “wrong,” “beneficial,” and “harmful.” Those concepts refer to the goals and purposes of living organisms engaged in a quest for self-preservation—and how different things impact that quest.

Answering the dilemma

Values are what a living organism pursues for the sake of self-preservation. Life is the final goal its other goals aim at. An organism’s life is its ultimate value.

Does this solve our ethical dilemma? Recall the challenge.

The general way we justify value judgments is by demonstrating that something is a valid means to an end. If you want to go for a jog, reason can tell you that putting on comfortable running shoes is good and that putting on high heels is bad. But how do you justify the end? Easy: by demonstrating that it is a valid means to some further end: going for a jog is good if your end is losing weight.

This process of means/end reasoning can’t go on forever, however. It must terminate in an ultimate value. But if your ultimate value is ultimate—if it’s not a means to some further end—it’s not clear how reason can justify it. If your ultimate value is what makes other things good, what makes your ultimate value good?

No other candidate for the status of ultimate value can answer that challenge: life can. Life is a means to an end—but the end that it serves is only itself. A living organism’s life is the actions it takes—actions aimed at preserving itself as an action-taking entity.

Think of your own life. You engage in a constant process of activities: eating, exercising, showering, working. These activities maintain your life and constitute your life.

Other candidates for the ultimate value see valuing as a linear process where the ultimate end is an unjustifiable stopping point. Working is good because it is a means to eating. Eating is good because it is a means to pleasure. But why is pleasure good? Just because.

Life is not a linear process but a circle. Working is good because it is a means to eating. Eating is good because it is a means to life. Life is good because it is a means to more life-promoting activities like working and eating. Etc., etc.

It’s not that life is good and therefore you should pursue it; it’s that only in relation to the pursuit of life can things be good. Those things are: the things that contribute to and constitute life.

Life is the process of valuing. Any other candidate for the title of ultimate value is either a means to or component of life (i.e., it is not genuinely ultimate) or it is at odds with life (i.e., it is not genuinely a value).

In this sense, life is an end-in-itself, every other value is a means to it, and it is a means to nothing further. It is, in other words, the ultimate value.

Not so fast!

Careful readers are probably wondering whether we’ve really established an objective morality.

After all, it might be true that other living organisms pursue their life as their ultimate value—but does that mean human beings have to? Isn’t there more to human life than simply staying alive?

What’s more, most people seem to be living just fine without morality. The focus on life might seem to justify a medical textbook, but why a moral code?

These are all good questions. And we’ll return to them next week.

3 Fun Things

A Quote

On the phenomenal level from which all science must proceed, life is nothing if not just the manifestation of apparent purposiveness and organic order in material systems. In the last analysis, the beast is not distinguishable from its dung save by the end-serving and integrating activities which unite it into an ordered, self-regulating, and single whole, and impart to the individual whole that unique independence from the vicissitudes of the environment and that unique power to hold its own by making internal adjustments, which all living organisms possess in some degree. —Gerd Sommerhoff, Systems Biology

A Resource

“Grounding Morality In Facts” with Harry Binswanger and Gregory Salmieri. Two experts on Ayn Rand’s philosophy elaborate on many of the themes in this week’s newsletter.

A Tweet

Effective Egoism 101

The conception of earthly idealism I champion was defined by Ayn Rand. Here are three key works that summarize her perspective:

Faith and Force: Destroyers of the Modern World by Ayn Rand

Causality vs. Duty by Ayn Rand

The Objectivist Ethics by Ayn Rand

Terrific explanation with concrete details of Ayn Rand's claim that the ultimate value for all living beings is life itself. I look forward to a further understanding and answers to those who would question such an all-time encompassing statement in future weeks.

I appreciate innovative thinkers who are able to consider real-life ethical dilemmas in terms of theories devised by their own observations and reasonings, even if it is not exactly in the same terms as described and evaluated by great thinkers such as Aristotle and Ayn Rand.

For example: Some years ago I met someone who has an effective way of addressing ethical dilemmas expressed by his friends; and he was able to do this by departing from the traditional “egoism vs altruism” as a fundamental alternative in ethical theory. He was able to identify more essential fundamental alternatives according to the facts he was provided.

I thought this was an impressive method of philosophic thinking. But what my question is: what exactly validates an original theory? If ethical theories could be originated for more specific ethical subject — say, the subject of character development — how can one test the validity of a proposed “ultimate value”? My first instinct is to take an inductive approach: to observe instances where such a value is present in successfully-matured characters, and not-present in characters who fail to mature. Do you have any insight on this issue?