Peter Singer Is Truly Awful

How Altruism Sacrifices the Best People to the Worst

The biggest barrier to secular thinkers embracing Effective Egoism is their belief that altruism is good. And who could doubt it? The word “altruism” calls to mind a vision of people who are warm, joyful, caring, benevolent, helpful. People whose lives are rich in meaning and whose strong moral character challenges and inspires us.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Altruism is moral poison.

Altruism ≠ helping others

Even though we’re taught to equate altruism with caring about others or helping others, that’s not how the term is used in practice. Consider this: who is more celebrated for their altruism—Moderna or Mother Teresa?

Thanks to its COVID-19 vaccine, Moderna has saved millions of lives. And yet no one calls it altruistic. Why not? Because it profited by helping others. In fact, *The Intercept* named Moderna and BioNTech executives the worst Americans of 2021 because…their revolutionary life-saving vaccines made them billionaires.

Mother Teresa, by contrast, is the symbol of altruism. Not because of how helpful she was to the world’s poor, but because of how much she sacrificed for the world’s poor.

Take a simpler example. Who would get the most moral credit? A billionaire who gave away a hundred million dollars to charity—or someone who gave his entire $50,000 life savings to charity? The person who helped the most—or the person who sacrificed the most?

Altruism = sacrificing yourself for others

Altruism is not a synonym for “nice.” It means, as one dictionary reports, “the belief in or practice of disinterested and selfless concern for the well-being of others.”

The term was coined by the positivist philosopher Auguste Comte to mean “other-ism”: a morality that demands living for others. Though people today seldom insist it is our “duty to annihilate ourselves if need be for the service of Humanity,” it is Comte they are echoing when they condemn Moderna.

Ayn Rand summarizes the doctrine this way:

What is the moral code of altruism? The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value.

Do not confuse altruism with kindness, good will or respect for the rights of others. These are not primaries, but consequences, which, in fact, altruism makes impossible. The irreducible primary of altruism, the basic absolute, is self-sacrifice—which means; self-immolation, self-abnegation, self-denial, self-destruction—which means: the self as a standard of evil, the selfless as a standard of the good.

What the champions of altruism say

What makes it hard to pin down the meaning of altruism is that few people today explicitly advocate it. Not because they don’t believe it—but because everyone believes it. It’s the same reason why you won’t find many Southerners defending racism in the early 1800s. There was no one to defend it against.

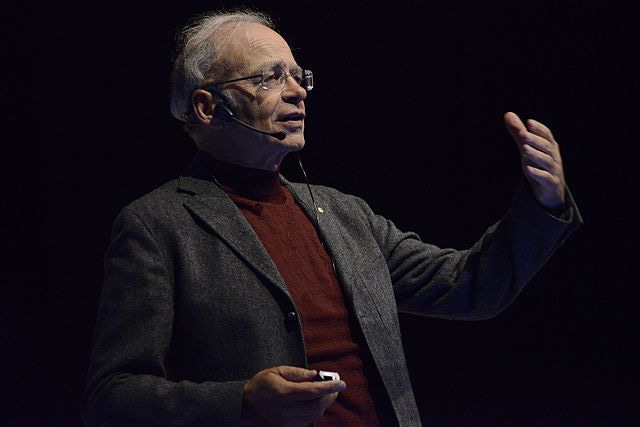

One person who does publicly champion altruism today is Peter Singer, who The New Yorker has called “the most influential living philosopher” and who was named by Time as one of the “100 most influential people in the world.” His argument is precisely that everyone believes altruism to be true, but almost no one seriously tries to live up to its demands—no one except the burgeoning movement of Effective Altruists.

In his popular book, The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, Singer describes some of the activities that characterize Effective Altruism, a movement that encourages people to “do the most good we can.”

Effective altruists do things like the following:

-Living modestly and donating a large part of their income—often much more than the traditional tenth, or tithe—to the most effective charities;

-Researching and discussing with others which charities are the most effective or drawing on research done by other independent evaluators;

-Choosing the career in which they can earn most, not in order to be able to live affluently but so that they can do more good;

-Talking to others, in person or online, about giving, so that the idea of effective altruism will spread;

-Giving part of their body—blood, bone marrow, or even a kidney—to a stranger.

By way of illustration, he tells the story of a promising philosophy student who abandons a career in philosophy to work on Wall Street so he would have more money to give away. He tells the story of Zell Kravinsky, who gave away most of his $45 million fortune and, convinced he had not sacrificed enough, donated a kidney to a stranger.

He tells us about a young woman named Julia Wise, who struggled with the decision of whether to have children: “she felt so strongly that her choice to donate or not donate meant the difference between someone else living or dying that she decided it would be immoral for her to have children. They would take too much of her time and money.” (Singer reassuringly says altruism is compatible with having children since they too might grow up to be altruists.)

What altruism requires of us is not the occasional donation to the Make a Wish Foundation. Indeed, Singer thinks it’s morally dubious to give money to make dying children happy when that same money could be used to stop other children from dying. But his main point is that altruism demands radical sacrifice. To take altruism seriously, you don’t need to give up everything—but you should give up virtually everything.

[I]n 1972, when I was a junior lecturer at University College, Oxford, I wrote an article called “Famine, Affluence and Morality” in which I argued that, given the great suffering that occurs during famines and similar disasters, we ought to give large proportions of our income to disaster relief funds. How much? There is no logical stopping place, I suggested, until we reach the point of marginal utility—that is, the point at which by giving more, one would cause oneself and one’s family to lose as much as the recipients of one’s aid would gain.

The argument for altruism

What could possibly justify this moral outlook? Why should you treat your career, your wealth, your children, your internal organs, your life as nothing more than a means to the ends of others? Don’t you matter? In his earlier book The Life You Can Save, Singer claims his radical conclusions follow from moral premises everyone accepts. Here’s his argument:

First premise: Suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad.

Second premise: If it is in your power to prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing something nearly as important, it is wrong not to do so.

Third premise: By donating to aid agencies, you can prevent suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care, without sacrificing anything nearly as important.

Conclusion?

[Y]ou must keep cutting back on unnecessary spending, and donating what you save, until you have reduced yourself to the point where if you give any more, you will be sacrificing something nearly as important as preventing malaria—like giving so much that you can no longer afford an adequate education for your own children.

How, asks Singer, can a nice house, outfits that make you feel attractive, romantic meals at fancy restaurants, a hard-won vacation to Telluride, or even a savings account large enough to provide enduring financial security be more important than the lives you could save by giving away that money? How can you justify living a middle-class lifestyle when your income could prevent the poorest people on earth from dying?

Singer’s conclusion makes many people uncomfortable, but they can’t spot any flaws in his reasoning. The trick is hidden in his second premise. Singer claims, “If it is in your power to prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing something nearly as important, it is wrong not to do so.” The question is: more important to whom? Isn’t my life more important to me than the life of a stranger I’ll never meet?

Singer’s basic assumption is that I should not value my own life more than the lives of other people. But why not? Placing priority on my own life doesn’t mean I regard other people as servants or resources I can exploit. On the contrary, to assert my right to exist for my own sake is to recognize that other people have a right to exist for their own sake. On that view, I won’t sacrifice for other people for the same reason I don’t expect them to sacrifice for me.

To the extent Singer’s second premise is plausible it’s because we take it to mean: if you can help someone in an emergency situation without great cost or risk to yourself, you should. And that’s true. Other human beings are values to us. Even strangers are fellow human beings, and absent evidence to the contrary, we see them as potential allies in the quest for happiness. We want them to thrive and to succeed. We don’t want them to suffer. If I see a child drowning and I’m in a position to save him, I will. Not from some sense of duty, not because some professor will castigate me for not helping, but from my love of my own life.

When you love your life, you love human potential and seek to encourage and honor that in action. To save a drowning child when there’s no significant danger to yourself is not a sacrifice. But that doesn’t mean you follow the kid home, and assume responsibility for his food, his housing, his education. It doesn’t mean that you abandon your career and travel around the world in search of drowning children.

Singer is pulling a bait and switch. He brings to mind situations where helping is not a sacrifice and then asks us to draw a moral principle that demands total sacrifice. Here is the correct principle: be loyal to your values, never sacrificing a greater value to a lower value. This may very well mean helping someone in an emergency, but it can’t mean treating human suffering and misfortune as such as a claim on your life.

The reason to help others is precisely because emergencies are rare and exceptional. You can provide aid in emergencies without diverting yourself from pursuing your own happiness. Most people, most of the time, to the extent a country is free, have the power to support their own lives. And they should. They should not surrender their own lives to us—and we shouldn’t surrender our lives to them.

For all their focus on global poverty, Effective Altruists rarely talk about the cause of that poverty. The reason that a billion people continue to live in extreme poverty is not because we’ve given too little to charity: it’s because they don’t live in free countries. If you truly wanted to do “the most good you can,” you wouldn’t promote Effective Altruism. You would promote freedom.

The injustice of altruism

All that said, the practitioners of Effective Altruists are in a sense an aberration. They try to faithfully implement altruism’s demand for sacrifice. But altruism really isn’t intended to be practiced. The best way to understand it is not as a code of morality, but as a psychological weapon.

When people invoke altruism, it’s usually not because they genuinely want to help others—it’s because they want to control and exploit you. And the point isn’t that they’re misusing altruism—it’s that this is what altruism is designed for.

Consider this: no one—not even Peter Singer—demands that you sacrifice yourself consistently. To practice altruism consistently would entail suicide, since every bite of food you take is needed more by someone else. A consistent altruist would be a dead altruist.

Altruists will let you get away with living most of the time. But when they want your wealth or your obedience? That’s when they’ll demand that you sacrifice. They will rely on your guilt. You don’t want to be selfish, do you? Who are you to object to my demands? You’re no moral paragon. You’ve been out there enjoying your life while others suffer—now it’s time to serve.

I once spoke to a young woman whose sick father is insisting that she place her life on hold to take care of him. Doesn’t she realize that’s her moral duty to the family? That is what altruism looks like. A truly moral person may ask for help. But to demand it as a duty? That is depraved, and yet it’s precisely what altruism preaches. If you are in need, other people are your servants.

You might wonder: aren’t those demanding others serve them being selfish? And isn’t that inconsistent with altruism? Economist Thomas Sowell once posed the puzzle this way: “I have never understood why it is ‘greed’ to want to keep the money you have earned but not greed to want to take somebody else’s money.”

In other words, if the good is the “non-good for me,” doesn’t that mean that we all should sacrifice—and that no one should be able to collect on those sacrifices? Isn’t altruism self-contradictory since you’re supposed to serve others, but from their own standpoint, they aren’t “others”? They are people bound by the same moral code, which says that the good is non-them? Rand puts the paradox this way:

Why is it moral to serve the happiness of others, but not your own? If enjoyment is a value, why is it moral when experienced by others, but immoral when experienced by you? If the sensation of eating a cake is a value, why is it an immoral indulgence in your stomach, but a moral goal for you to achieve in the stomach of others? Why is it immoral for you to desire, but moral for others to do so? Why is it immoral to produce a value and keep it, but moral to give it away? And if it is not moral for you to keep a value, why is it moral for others to accept it? If you are selfless and virtuous when you give it, are they not selfish and vicious when they take it? Does virtue consist of serving vice? Is the moral purpose of those who are good, self-immolation for the sake of those who are evil?

But, Rand goes on to point out, this is only a paradox—not a contradiction. The morality of altruism allows you to collect sacrifices and gain values—provided you don’t earn them. If you’re a producer, you don’t have a right to what you produce. That’s greedy. But if you’re a parasite who produces nothing? That is precisely what gives you a moral right to what others produce. “It is immoral to earn, but moral to mooch—it is the parasites who are the moral justification for the existence of the producers, but the existence of the parasites is an end in itself.”

According to altruism, if you earn values, you have to give them up. What entitles you to values? The fact you didn’t earn them. A need you’re unable or unwilling to satisfy is what entitles you to have your needs fulfilled by other people’s efforts and at other people’s expense. A lazy bum who makes excuses for his failures is morally superior to the affluent relatives he mooches off of—he is a needy victim while they are selfish and greedy for only sacrificing a small portion of their wealth for him. This is the actual meaning of “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”

When altruists say they are champions of “the good of others” what they really mean is, “the worst people get to demand to have their wishes satisfied by the sacrifices of the best people.”

This isn’t morality. This is evil and injustice masquerading as morality. Secular thinkers need to reject this Dark Ages morality the same way they’ve rejected the rest of the Dark Ages mentality. But to do that requires a moral alternative: Effective Egoism.

3 Fun Things

A Quote

“Now there is one word—a single word—which can blast the morality of altruism out of existence and which it cannot withstand—the word: ‘Why?’ Why must man live for the sake of others? Why must he be a sacrificial animal? Why is that the good? There is no earthly reason for it—and, ladies and gentlemen, in the whole history of philosophy no earthly reason has ever been given.”

—Ayn Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It

A Resource

“The Evil of Altruism” by Onkar Ghate. Onkar reveals the religious roots of altruism, and the destruction and injustice it unleashes.

A Tweet

Effective Egoism 101

The conception of earthly idealism I champion was defined by Ayn Rand. Here are three key works that summarize her perspective:

Faith and Force: Destroyers of the Modern World by Ayn Rand

Causality vs. Duty by Ayn Rand

The Objectivist Ethics by Ayn Rand

>The trick is hidden in his second premise.

No, the first premise is basic.

>[Singer]Suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad.

The psychological results of altruism may be observed in the fact that a great many people approach the subject of ethics by....A nightmare view of existence—since he believes that men are trapped in a “malevolent universe” where disasters are the constant and primary concern of their lives.

-Rand, Ethics Of Emergencies

>Peter Singer is truly awful.

He is an evil death-worshipper. "Truly awful" is for shoes that pinch your toes.

And notice that the conventional definition of altruism implicitly agrees with Rand that it's self-sacifice. "Helping others" is an evasion of the helper. He is not to be considered. He is to be sacrificed.

All praise to Ayn Rand who not only unlocked the key to this evil madness, but wrote the best book in history pointing it out, and most of all had the courage to continue trumpeting the truth of this villainous moral code to an un-thinking world her whole life.