What is Effective Egoism?

An Objective Morality for Secular Thinkers

Religionists often claim that without God, there cannot be an objective morality. And that obviously would be a disaster. If people went around lying, cheating, stealing, raping, and killing, human life would be impossible.

But what that argument shows is that anyone who values his life has plenty of earthly reasons for championing morality. What does God add?

One thing He might add is: eternal punishment and eternal rewards. But Heaven and Hell aren’t needed to give us a stake in morality—an earthly Heaven and an earthly Hell are sufficient. The reason most people tell the truth and respect others’ rights isn’t because they’re terrified of eternal damnation: it’s because anyone who lies, cheats, and steals ends up miserable or worse.

God isn’t required for morality. Morality is a vital instruction manual for how to live well—and there’s no mystery to why we should want to live well. We only need God if we equate morality with a bunch of senseless duties that have nothing to do with our life and happiness. It’s clear how lying puts us at odds with other people and makes us vulnerable to being exposed—it’s anything but clear why we shouldn’t masturbate or eat meat on Fridays.

“Because God said so”? That doesn’t make morality objective: a morality based on God’s say-so is supernatural subjectivism. It says that morality isn’t based on facts about the world, but the arbitrary command of an authority. It’s not wrong, on this view, to murder my child if God commands me to murder my child, no matter how pointless and senseless that command appears to be.

What actually makes morality objective is not some authority’s dictates, but that its guidance is based on facts rather than feelings (yours, mine, society’s, God’s).

What facts give rise to our need for morality? And what specific guidance would a fact-based, earthly morality give us?

In this article, we’ll see that:

Evaluative concepts (e.g., “good,” “bad”) aren’t mystical or arbitrary—they are based on the fact that living organisms act to achieve goals in order to survive.

Human beings need guidance in order to survive—and this guidance is precisely what a rational morality is designed to provide.

If the purpose of morality is to teach us how to live, then a rational morality is egoistic: it upholds the pursuit of self-interest as the proper ethical goal for human beings to pursue.

Self-interest doesn’t consist of amassing money, status, and power without regard for the interests of others—it consists of securing profound material and spiritual values (including love and friendship), neither sacrificing yourself to others nor others to yourself.

There is an objective morality—an earthly ideal that does not require faith in the supernatural. But that morality looks nothing like the conventional morality our Christianized culture takes for granted.

I call it: Effective Egoism.

Solving History’s Greatest Ethical Dilemma: How do you justify an ultimate value?

For more than 2,000 years, ethical thinkers have struggled with a riddle. How do you justify a moral theory’s ultimate value?

An ultimate value is what an ethical theory identifies as the highest good—and the standard for assessing other things as good or bad. Is it money? Honor? Pleasure? The greatest happiness for the greatest number? Doing God’s will?

The problem comes once you’ve asserted something as an ultimate value: if it is the standard of what’s good, what makes it good? It makes sense to say that food, sex, and roller coasters are good because they produce pleasure. But why make pleasure the standard? Why not the greatest happiness for the greatest number? It seems like you need to appeal to something beyond pleasure to say that it’s good. And, yet, if there were something beyond pleasure you could appeal to, then pleasure wouldn’t be ultimate.

Thinkers have responded to this riddle in two main ways. One way is to say that their ultimate value is intrinsically valuable. But that’s not really different from saying, “I can’t prove this is valuable, but I just feel like it is.” The other way is to look at all these conflicting claims about intrinsic values and to conclude that ethics is inherently arbitrary.

But there’s something wrong with this entire approach to ethics. We can’t start by asking which ultimate value we should pursue. Following Ayn Rand, we need to ask a more basic question: what are values?

Once we’ve answered that, it turns out we can settle the issue of what is the right ultimate value without arbitrarily appealing to some “intrinsic” value—and without conceding that ethics is arbitrary.

Values = goals + stakes

To make sense of something as a value, we need to see an entity acting to gain (or keep) it. A value is an object of goal-directed action. Take away goal-directed action, and it simply doesn’t make sense to talk about values. There are no values on Venus.

But action by itself isn’t enough. To make sense of something as a value, we also need to see that the entity acting to gain it is affected by the outcome. That it has skin in the game. That it’s taking an action with stakes.

To drive this point home, Rand has us try to imagine an immortal, indestructible robot, “an entity which moves and acts, but which cannot be affected by anything, which cannot be changed in any respect, which cannot be damaged, injured or destroyed. Such an entity would not be able to have any values.” Why not? Because “it would have nothing to gain or to lose; it could not regard anything as for or against it, as serving or threatening its welfare, as fulfilling or frustrating its interests. It could have no interests and no goals.”

So where do we see goal-directed action with stakes? We see it with things that aren’t immortal or indestructible. With things that can be damaged, injured, and destroyed. With living organisms.

Life is goal-directed action with stakes

There is a radical difference between living organisms and everything else in nature: living organisms pursue goals. And not just any goals. Across the countless activities that make up a living being’s way of life, the central concern that explains its actions is: the struggle for survival.

Living organisms act to achieve goals that sustain their lives. If they don’t—or if they fail to achieve their goals—they slow down, weaken, malfunction, suffer, and die. If values require goal-directed action with stakes, then life just is goal-directed action with stakes.

“On the phenomenal level from which all science must proceed, life is nothing if not just the manifestation of apparent purposiveness and organic order in material systems. In the last analysis, the beast is not distinguishable from its dung save by the end-serving and integrating activities which unite it into an ordered, self-regulating, and single whole, and impart to the individual whole that unique independence from the vicissitudes of the environment and that unique power to hold its own by making internal adjustments, which all living organisms possess in some degree.”

—Gerd Sommerhoff, Systems Biology

There is nothing mystical or arbitrary about values and evaluative concepts like “good,” “bad,” “right,” “wrong,” “beneficial,” and “harmful.” Those concepts refer to the goals and purposes of living organisms engaged in a quest for self-preservation—and how different things impact that quest.

Answering the dilemma

Values are what a living organism pursues for the sake of self-preservation. Life is the final goal its other goals aim at. An organism’s life is its ultimate value.

Does this solve our ethical dilemma? Recall the challenge.

The general way we justify value judgments is by demonstrating that something is a valid means to an end. If you want to go for a jog, reason can tell you that putting on comfortable running shoes is good and that putting on high heels is bad. But how do you justify the end? Easy: by demonstrating that it is a valid means to some further end: going for a jog is good if your end is losing weight.

This process of means/end reasoning can’t go on forever, however. It must terminate in an ultimate value. But if your ultimate value is ultimate—if it’s not a means to some further end—it’s not clear how reason can justify it. If your ultimate value is what makes other things good, what makes your ultimate value good?

No other candidate for the status of ultimate value can answer that challenge: life can. Life is a means to an end—but the end that it serves is only itself. A living organism’s life is the actions it takes—actions aimed at preserving itself as an action-taking entity.

"Being alive, selves work to stay alive, doing work that we are able to do because we are alive. Our means and ends are circular. We engage in means-to-ends behavior most fundamentally toward the end of maintaining our self-regenerative means.”

—Jeremy Sherman, Neither Ghost Nor Machine

Think of your own life. You engage in a constant process of activities: eating, exercising, showering, working. These activities maintain your life and constitute your life.

Other candidates for the ultimate value see valuing as a linear process where the ultimate end is an unjustifiable stopping point. Working is good because it is a means to eating. Eating is good because it is a means to pleasure. But why is pleasure good? Just because.

Life is not a linear process but a circle. Working is good because it is a means to eating. Eating is good because it is a means to life. Life is good because it is a means to more life-promoting activities like working and eating. Etc., etc.

It’s not that life is good and therefore you should pursue it; it’s that only in relation to the pursuit of life can things be good. Those things are: the things that contribute to and constitute life.

Life is the process of valuing. Any other candidate for the title of ultimate value is either a means to or component of life (i.e., it is not genuinely ultimate) or it is at odds with life (i.e., it is not genuinely a value).

In this sense, life is an end-in-itself, every other value is a means to it, and it is a means to nothing further. It is, in other words, the ultimate value.

What about Hume?

How does the above argument answer Hume’s famous claim that you cannot derive an “ought” from an “is”? In A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume writes:

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remark’d, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surpriz’d to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation,’tis necessary that it shou’d be observ’d and explain’d; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it.

If Hume proved anything, it’s that you can’t deduce an ought from an is. But as philosopher Harry Binswanger has pointed out, it’s a truism that no syllogism can have a term in its conclusion that isn’t in its premises. You can’t derive facts a conclusion about bananas from non-banana premises? Okay. So what?

Every deduction gets its premises ultimately from observation. The question isn’t whether we can deduce an ought from is but whether there are observable facts that give rise to evaluative concepts.

And that’s precisely what we’ve seen: that the life-or-death alternative faced by living organisms allows and requires us to form evaluative concepts. Things are good or bad insofar as they impact an organism’s pursuit of its ultimate value: its life.

In answer to those philosophers who claim that no relation can be established between ultimate ends or values and the facts of reality, let me stress that the fact that living entities exist and function necessitates the existence of values and of an ultimate value which for any given living entity is its own life. Thus the validation of value judgments is to be achieved by reference to the facts of reality. The fact that a living entity is, determines what it ought to do. So much for the issue of the relation between ‘is’ and ‘ought.’”

—Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness

But how does this answer Hume? Couldn’t a Humean object that the pursuit of life is subjective because someone might have the opposite goal?

To see the error, imagine someone said, "I want knowledge, therefore I ought to think." Would that be subjective? No. Because seeking knowledge is the precondition of criticizing things as subjective.

You don’t have to pursue knowledge, but it’s only the pursuit of knowledge that provides a basis for distinguishing between better and worse ways of knowing. The quest for knowledge gives rise to epistemological normativity.

What I’ve argued is that the quest for life gives rise to ethical normativity. You don’t have to pursue life—more on this below—but it’s only the pursuit of life that provides a basis for distinguish better and worse ways of living. If death is your goal, you don’t need ethical guidance—in the same way that if ignorance is your goal, you don’t need epistemological guidance.

Pursuing life is not subjective because the alternative is not some other set of possible values but no values at all, i.e., death.

If you choose to live, you need a moral code to teach you how to flourish

We’ve seen that values arise from the fundamental alternative living organisms face between existence or non-existence. Living beings need values in order to maintain their ultimate value: their life.

But that leaves some crucial questions to answer. Even if it’s true that other living organisms pursue their life as their ultimate value, does that mean human beings have to? Isn’t there more to human life than simply staying alive? And plenty of people seem to live just fine without morality—doesn’t the existence of octogenarian thieves and murderers pose a big problem for a life-based morality?

Not Avoiding Death, but Optimizing for Life

A moral code is a guide for realizing your ultimate value. Plenty of people avoid dying for a long time without a moral code, but if life is your ultimate value, the aim is not to avoid the morgue. It’s to optimize for life.

Optimizing for life means recognizing that you have complex material and psychological needs that require ongoing attention.

You need food, clothing, shelter, medicine to secure your physical survival. And you also need the things that allow you to meet those needs: tools, energy, transportation, and an entire knowledge and production system that allows human beings to create ever-more powerful and abundant tools, energy, and transportation.

You meet your material needs by exercising thought and effort—reason and production. You use your mind to discover the way the world works, and you use that knowledge to reshape the world to achieve your purposes.

But to carry out that life-promoting process, you also have profound psychological needs.

“Just as man’s physical survival depends on his own effort, so does his psychological survival. Man faces two corollary, interdependent fields of action in which a constant exercise of choice and a constant creative process are demanded of him: the world around him and his own soul. . . . Just as he has to produce the material values he needs to sustain his life, so he has to acquire the values of character that enable him to sustain it and that make his life worth living. He is born without the knowledge of either. He has to discover both—and translate them into reality—and survive by shaping the world and himself in the image of his values.”

—Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto

Think of someone who is riddled with self-doubt and depression. He’s less likely to undertake demanding projects. He may even find it difficult to hold down a low-level job and attend to basic needs like brushing his teeth and showering. Without the sense that life is worth living, he’s less able to take the actions necessary to live.

If life is your goal, cultivating a sense of purpose, self-confidence, and self-worth are not luxuries, but vital components of optimal functioning. That’s not something you can get out of the way during the workweek, leaving you free to pursue other goals on the weekend. To optimize for life, all of your energy and effort must be directed toward building, strengthening, and enjoying your life.

The purpose of morality is to teach you how to do that.

Optimizing for Life Requires a Morality of Life

Other organisms act automatically to support their lives. But human beings aren’t born knowing how to live. As a rational being, you have an unlimited potential for understanding the world, but all of your knowledge is hard-won: you have no instincts, no automatic, unerring knowledge to guide you.

Much of the knowledge your survival requires is small-scale and tactical. Don’t touch a hot stove. Look both ways before crossing the street. But the core of optimal living is long-range and strategic: it’s about how to chart a course that spans decades and secures your material and psychological flourishing.

How do you chart such a course? That’s the purpose of a moral code. It describes in abstract terms what a flourishing human life consists of, giving you a blueprint for building your distinctive life.

We’ve already touched on some of the universal values and virtues that add up to a human life. As organisms who survive through thought and production, and who must have the self-confidence and self-worth to engage in thought and production, our three cardinal values are: reason, purpose, and self-esteem. We have to cultivate our minds, actively work to achieve life-supporting values, and build a character that makes us able to live and worthy of happiness.

Achieving these values requires a corresponding set of virtues: rationality, productiveness, and pride. Rationality means the commitment to use reason as our only guide to knowledge, values, and action. Productiveness means building our lives around a fulfilling productive career. Pride means our commitment to cultivating the best possible moral character.

And, because other people are both enormous potential values and enormous potential threats, a pro-life morality requires the virtue of justice: judging people rationally and treating them as they deserve. This means praising and forming mutually fulfilling relationships with good people—and avoiding, ostracizing, and (in criminal cases) punishing bad people.

Existentially, living according to a pro-life moral code is how we secure our existence. Psychologically, the insignia of securing our existence through moral action is: happiness.

Morality’s Authority

Why be moral? Religious thinkers often equate an objective morality with a morality that you in some sense have to follow. It’s a set of duties you must obey—or else it is, in Christian apologist William Lane Craig’s words, “just a human convention” that is “wholly subjective.”

It’s understandable why religious thinkers believe morality must consist of unchosen duties: otherwise, you would have no reason to obey the senseless rules their moral code imposes.

But it is all too clear why you should follow a pro-life morality: your life (and happiness) depends on it. You have everything to gain from such a code—and nothing to lose. Indeed, you have everything to lose from not following such a code.

Nevertheless, following a pro-life morality is not a duty. You need morality only if you choose to live. If you don’t choose to value your life, then you don’t need morality’s guidance. You don’t need any guidance. You’re free to stop acting and let nature take its course.

“One does not have to value one’s life, but only life can ground the means-end hierarchy, only life can be an end-in-itself. For man, life is potentially an ultimate value, and nothing else is, but actualizing that potential is up to one’s choice.”

—Harry Binswanger, “Life-Based Teleology and the Foundations of Ethics”

This is not some “get out of morality free” card that prevents us from judging death-seekers or leaves us at their mercy. A person who does not choose to live has made himself an enemy of those of us who do value our lives. Though he cannot be swayed by moral reasoning, which depends on his desire to live, we can nevertheless refuse to deal with him. And, if he attempts to impose his self-destructive course on us by force, we will act to stop him by force.

Morality has profound authority: you must follow its principles—if you want to live. Choice doesn’t make morality subjective or conventional. Morality’s guidance is not based on whim or convention, but on ineradicable facts about the nature of human life. Moral principles are absolute. You do not get to choose the content of morality—you only get to choose whether to value this world and all it has to offer, or to value nothing at all.

The Human Way of Life

Let’s summarize: An organism’s life is its ultimate value. But human beings have free will. We don’t automatically value our lives, and we don’t automatically know how to sustain them. If we choose to live, then we need the guidance of a pro-life moral code. An objective morality teaches us how to realize our only possible ultimate value: our life.

But this raises a vital question. If we don’t know automatically how to sustain our life, how do we discover it? Our physical and psychological needs are complex, multi-faceted, holistic, and long range. We can’t just look at a given choice and know whether it will promote or undercut our life. How does a pro-life moral code solve this problem?

How do we objectively derive the content of a pro-life moral code?

An Objective Moral Standard

Every organism has a way of life distinctive to its species—a way of life organized around the struggle for survival. This way of life allows scientists to explain and predict the structures and activities of an organism. The hawk circling my backyard has wings because flying is central to how a hawk secures its food.

A way of life also acts as a standard of value that allows us to assess things as good or bad for an organism. Breaking a wing is bad for the hawk because it makes it less capable of taking the life-promoting actions a hawk’s life requires.

What is the human way of life? Human beings survive by reason. We use our minds to understand the world and transform it through productive actions to meet our needs.

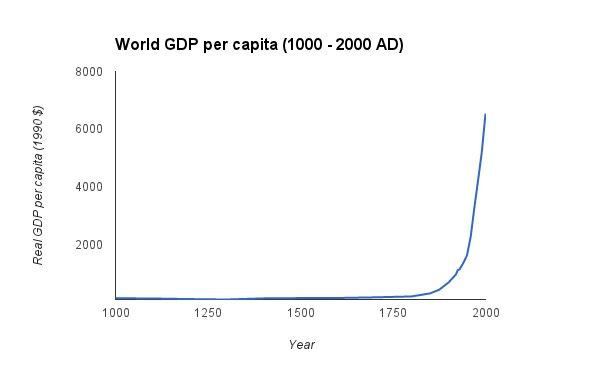

This is the ultimate meaning of the industrial revolution. The skyrocketing standard of living brought about by scientific breakthroughs and technological innovations demonstrated that reason is our basic means of survival.

In order to achieve the ultimate value of your life you need an abstract standard of value to guide your actions. Ayn Rand called that standard “man’s life”:

Since reason is man’s basic means of survival, that which is proper to the life of a rational being is the good; that which negates, opposes or destroys it is the evil.

The point is not that you should survive by reason rather than some other way. It’s that reason is how you survive—and so if life is your goal, you should live by reason because there is no other way to live. Even people who seem to get by irrationally have to count on the rationality of others: a nation of full-time thieves would have nothing to steal.

What It Means to Live by Reason

What does it mean to “live by reason”? Here’s what it doesn’t mean: emulate Star Trek’s Spock, and turn yourself into an emotionless utilitarian calculator.

A better symbol is the entrepreneur. An entrepreneur uses reason to project new and better ways of doing things. He formulates a vision of a future worth creating, and then actively works to build that future. He moves forward based on his own independent judgment, overcoming obstacles and ignoring the doubters. His goals aren’t small scale and conventional, but creative and ambitious.

“An emotion is an automatic response, an automatic effect of man’s value premises. An effect, not a cause. There is no necessary clash, no dichotomy between man’s reason and his emotions—provided he observes their proper relationship. A rational man knows—or makes it a point to discover—the source of his emotions, the basic premises from which they come; if his premises are wrong, he corrects them. He never acts on emotions for which he cannot account, the meaning of which he does not understand. In appraising a situation, he knows why he reacts as he does and whether he is right. He has no inner conflicts, his mind and his emotions are integrated, his consciousness is in perfect harmony. His emotions are not his enemies, they are his means of enjoying life. But they are not his guide; the guide is his mind.”

—Ayn Rand, “The Playboy Interview”

To live by reason is not to pursue knowledge as end in itself, nor is it to become a cold, calculating machine. To live by reason is to actively pursue ambitious material and spiritual values—values such as a fulfilling career, self-esteem, romantic love, and soul-nourishing art. It’s to use reason to project a life that you want to live—your specific form of the human way of life—and to make that life real.

But to make it real, to achieve rational values, requires acting rationally. It requires cultivating rational virtues.

The Virtues of Reason

Pragmatism is impractical: you can’t foresee all of the consequences of your actions, and all-too-often choices that seem low-stakes and innocuous turn out to have major consequences you did not predict.

Virtues solve this problem. They are causal principles that identify the actions that lead to life-promoting values. They tell you which choices will lead to long-range achievement and success, and which will lead to long-range frustration and failure.

Because reason is your basic means of survival, your fundamental virtue is rationality: the virtue of using reason as your only guide to knowledge, values, and actions.

Every other virtue is an aspect of rationality: it specifies what it means to be rational in light of some specific fact about human nature. This includes virtues such as honesty, integrity, independence, productiveness, justice, and pride.

For example, the virtue of independence says that because reason is an individual faculty, you should live by your own judgment and by the work of your own mind.

Independence doesn’t mean that you ignore other people, refuse to learn from them, or refuse to cooperate with them. It means that because no one else can do your thinking and your living for you, you must take responsibility for your own thinking and life, recognizing that dependence in any form cripples your ability to thrive.

The life-or-death importance of independence isn’t obvious. Many people believe it’s safer to obey some authority rather than the judgment of their own mind. Many believe it’s easier to passively copy the routines laid down by others rather than discover how to do good work. Some seek to bypass the need to work altogether, mooching off of friends, relatives, or the state—or simply taking what they want from others by force.

But in all of these cases, the dependent is surrendering control over his life. He’s blindly placing himself at the mercy of others—of their ignorance, their irrationality, their generosity, their gullibility, their weakness. He’s made himself a passenger in a vehicle driven God knows where but God knows who.

Virtue is not its own reward. Virtue is a practical necessity: to act virtuously is to guarantee that you’ll achieve the values human life requires, over time and barring accidents. Vice, by contrast, guarantees failure, conflict, suffering, loss.

The Objectivity of Happiness

We’ve seen that the purpose of morality is objective: morality is a guide to achieving the ultimate value of your life. We’ve also seen that morality’s guidance is objective: human life has specific requirements rooted in our nature as rational beings.

But there is one further implication to draw attention to: happiness has objective requirements.

Today, happiness is seen as inherently subjective. But happiness simply is the psychological state of achieving your values, and it is only values aligned with a pro-life morality that can be fully realized.

A rational moral code gives you an integrated set of values and virtues that add up to a human life. Without such a code, you may achieve some of your values, but only at the frustration of others. You’ll be pulled in different directions, and it’s precisely this state of conflict that is the mark of unhappiness. Happiness is the state of unconflicted fulfillment.

The convergence of a pro-life morality and happiness is not some accidental bonus for pursuing your life as your ultimate value. Happiness is the emotional state of successful living. We don’t pursue happiness in order to live or pursue life in order to achieve happiness.

The pursuit of happiness is the pursuit of life. They are two perspectives on a single achievement. Happiness is how we experience the fact that life is an end in itself.

Effective Egoism

In ancient Greece, morality was seen as a guide to living well. Ethics was egoistic: morality was not a constraint on your self-interest but a blueprint for identifying your genuine interests—the values and virtues that lead to happiness.

Christianity turned the purpose of morality on its head. Morality became, not a guide to achieving your interests, but a nag scolding you to sacrifice your interests: serve God, serve your neighbor, serve your enemy.

“Thus from faith flow forth love and joy in the Lord, and from love a cheerful, willing, free spirit, disposed to serve our neighbor voluntarily, without taking any account of gratitude or ingratitude, praise or blame, gain or loss. Its object is not to lay men under obligations, nor does it distinguish between friends and enemies, or look to gratitude or ingratitude, but more freely and willingly spends itself and its goods, whether it loses them through ingratitude, or gains goodwill.”

—Martin Luther, Concerning Christian Liberty

The Enlightenment undermined religion’s authority as a guide to knowledge and social organization. But Enlightenment thinkers were unable to formulate a secular moral ideal. As religion’s influence waned, many worried that the “death of God” would unleash nihilism. Instead of throwing out religious morality, thinkers like the French philosopher Auguste Comte secularized it.

Comte named his secular “religion of humanity” altruism—literally, “other-ism.” A truly virtuous person, said Comte’s follower John Bridges, believes that “Our duty is to annihilate ourselves if need be for the service of Humanity.”

Ayn Rand called altruism a morality of death, and countered that “The purpose of morality is to teach you, not to suffer and die, but to enjoy yourself and live.” Embracing a pro-life morality means embracing self-interest as your moral goal.

Who benefits?

So far, in our quest for an objective morality, we’ve seen that values are what living organisms pursue to sustain their lives. Human beings don’t have to value our lives—that is a choice. But if we do choose to live, we need a pro-life moral code to teach us how to implement that choice. We need a pro-life moral code that includes values such as reason, purpose, and self-esteem, and virtues such as rationality, productiveness, justice, and pride.

Now we can complete the case for an objective morality by highlighting a crucial corollary of the foregoing: if your life is your ultimate value, then self-interest is a moral imperative.

To say that self-interest is a corollary of holding your life as your ultimate value is to say there’s no additional argument for egoism. Egoism stresses only this much: if you choose and achieve life-promoting values, there are no grounds for saying you should then throw them away. And yet that is precisely what altruism demands.

Altruism says that if you work to bring values into existence—if you grow food, if you earn money, if you build a billion dollar company, your moral obligation is give it up. For whom? For anyone who didn’t earn it. Why do they deserve it? Precisely because they didn’t earn it.

“Why is it moral to serve the happiness of others, but not your own? If enjoyment is a value, why is it moral when experienced by others, but immoral when experienced by you? If the sensation of eating a cake is a value, why is it an immoral indulgence in your stomach, but a moral goal for you to achieve in the stomach of others? Why is it immoral for you to desire, but moral for others to do so? Why is it immoral to produce a value and keep it, but moral to give it away? And if it is not moral for you to keep a value, why is it moral for others to accept it? If you are selfless and virtuous when you give it, are they not selfish and vicious when they take it? Does virtue consist of serving vice? Is the moral purpose of those who are good, self-immolation for the sake of those who are evil?”

—Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

Altruism is a morality of injustice: if you exercise the virtues required to live, you become a servant of those who don’t. According to altruism, it is the meek, not the virtuous, who shall inherit the earth.

The self-interest straw man

People do not accept altruism because it offers compelling arguments. They accept it either because they want to be the ones collecting your sacrifices—or because they believe that the only alternative is the warped view of self-interest altruism has erected as a straw man.

Altruism equates your interests, not with reason, purpose, and self-esteem, but money, status, and power. To pursue your self-interest is to maximize these narrow interests without considering the impact of your actions on other people—or even the long-term impact on you.

No one really believes that unscrupulously piling up fame and cash is a desirable way to live. Most of us want our kids to be happy—we don’t teach them to become Kim Kardashian or Bernie Madoff. But the alternative to Kardashian and Madoff is not a selfless servant looking to be exploited by others—it’s to become an Effective Egoist.

What is Effective Egoism? The short version: an Effective Egoist dedicates himself to a pro-life moral ideal in order to achieve and enjoy his own life and happiness, neither sacrificing himself to others nor others to himself.

The symbols of Effective Egoism are not Kim Kardashian and Bernie Madoff but the intransigence of a Frederick Douglass and the curiosity of a Richard Feynman and the passion of a Steve Jobs and the courage of a Jackie Robinson and the adventurousness of an Ernest Shackleton and the independence of an Alexander Hamilton and the creative intelligence of a Maria Montessori and the ambition of a Jeff Bezos. It is, for those who have read Ayn Rand’s novels, Dagny Taggart, Howard Roark, Francisco D’Anconia, Hank Rearden, and John Galt.

Effective Egoism is not psychological egoism. Psychological egoism is the view that human beings always seek our own interests. Effective egoism is the moral theory that says human beings should seek our own interests—and that, all too often, we don’t.

Effective Egoism requires valuing other people. Your own life is your primary value, not your only value. Your interests in part consist of the interests of the people you care about: your friends, your lover, your children. Creating mutually fulfilling relationships with others and taking joy in their existence is a vital part of human flourishing.

Effective Egoism requires virtue. To say that egoism is a corollary of a pro-life moral code is to say that it cannot be severed from that moral code and treated as a primary. The person who is “out for himself” without the guidance of moral principles is not an egoist. He’s a pragmatist or a predator. And what he achieves is not his interests, but his own destruction.

Effective Egoism recognizes that human interests don’t clash. Human life doesn’t require sacrifice because we survive through thought and production. Even seeming conflicts, such as competition between businesses, are nested inside a wider context of shared interests: a shared interest in freedom. Human beings flourish through forming win/win alliances and mutually fulfilling relationships. Interests only “clash” when people desire the unearned and undeserved—but desiring the unearned and undeserved is not actually to your interest.

Summarizing the Argument

There is a secular morality of reason: Effective Egoism.

Values are what living organisms pursue to maintain their ultimate value: their life.

Human beings need a pro-life moral code if they choose to live.

A pro-life moral code identifies the fundamental values and virtues that make up your genuine interests: values that include reason, purpose, and self-esteem, and virtues that include rationality, independence, honesty, integrity, productiveness, justice, and pride.

A pro-life moral code is egoistic: it says that you should benefit from your own moral action, neither sacrificing yourself to others nor others to yourself.

For more, see my forthcoming book Effective Egoism: An Individualist’s Guide to Pride, Purpose, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

Effective Egoism 101

The conception of earthly idealism I champion was defined by Ayn Rand. Here are three key works that summarize her perspective:

Faith and Force: Destroyers of the Modern World by Ayn Rand

Causality vs. Duty by Ayn Rand

The Objectivist Ethics by Ayn Rand

So looking forward to reading your book, this essay has already helped me understand some of the principles of objectivism that I was struggling with.

This is a really intriguing idea. Two criticisms though. Wouldn't this justify the ability to get away with any self serving crimes that you could get away with? As in if no one would find out, you could steal a million dollars.

Also I don't see how a society like this could field armies. Being a soldier is terrible for life but sometimes necessary for a society