William Lane Craig’s really bad case against secular morality

“In my experience, the moral argument is the most effective of all the arguments for the existence of God.” So says William Lane Craig, the ultra-popular Christian apologist who has made a career out of recycling such hits as, “If God doesn’t exist, who created the universe?”

But on this issue, Craig is right: morality is where secular thinkers are weakest. While atheists have effectively exposed the logical fallacies and scientific distortions behind the cosmological arguments, ontological arguments, and design arguments, on the issue of morality, they too often play defense—or resort to the laziest response of all: pillorying Christian hypocrisy.

Even the better responses—Christopher Hitchens observing that, no, infinite punishment for intellectual integrity is not just and loving—fail to deliver what matters most: a positive account of an objective morality.

Craig’s whole game is to cash in on the fact that human beings need such an account, and atheists have failed to deliver it. But that doesn’t change the fact that Craig’s own arguments are awful. Astonishingly, embarrassingly awful.

In his book On Guard: Defending Your Faith with Reason and Precision, Craig argues that if God doesn’t exist, life has no meaning, no purpose, and no value. As a result, atheism can offer no objective morality—it can only appeal to social convention and arbitrary personal preference.

But it turns out that Craig’s entire argument falls apart once you realize that it all rests on a simple gimmick: taking God’s perspective as the measuring stick for what meaning, purpose, and value must consist of.

tl;dr: Craig doesn’t prove that you need God for an objective morality—he defines away any possibility of a this-worldly objective morality. But in the process he undermines his own claim to an objective morality.

Meaning Without God

“Meaning,” says Craig, “has to do with significance, why something matters.” So it does. And there’s no mystery why my life should matter to me. Without my life, I don’t exist. Life is the precondition for anything that might matter to me, and the things that matter to me are all means to and constituents of my life.

Not so fast, says Craig. Did you know that human beings…die? “If each individual person passes out of existence when he dies, then what ultimate meaning can be given to his life? . . . This is the horror of modern man: Because he ends in nothing, he is nothing.”

The trick is with the word “ultimate.” “Ultimate” has two very different senses. The first sense refers to something “basic or fundamental.” In ethics, we are concerned with this sense of “ultimate”: we need to identify the fundamental value or good that makes other things valuable or good.

For example, Aristotle starts the Nicomachean Ethics by sketching out the criteria an ultimate good has to meet:

If, then, the things achievable by action have some end that we wish for because of itself, and we wish for other things because of this end, and we do not choose everything because of something else (for if we do, it will go on without limit, so that desire will prove to be empty and futile), it is clear that, this end will be the good, that is to say, the best good.

In my essay “Solving History’s Greatest Ethical Dilemma: How do you justify an ultimate value?”, I explain how an organism’s life is the only thing that meets these criteria. Life is an end in itself, everything else valuable is a means to it, and it is a means to nothing beyond itself.

Craig, however, has a different sense of “ultimate” in mind: not “basic or fundamental” but “happening at the end of a process.” His question amounts to, “What is the meaning of your life once you’re dead?”

But the fact that life has no meaning to the dead doesn’t undermine that it has meaning to the living. To experience something as meaningful is to experience it as an end in itself—as something worth having for its own sake. The meaning of a lifelong romance isn’t what happens at the end—it’s not the grief that you experience when your partner dies—it’s the daily joy the relationship brought you while your partner was alive.

If no moment can be meaningful in and of itself, then no eternity of such moments can be meaningful. An infinite series of zero still adds up to zero. Craig senses this because he goes on to say:

[I]t’s important to see that man needs more than just immortality for life to be meaningful. Mere duration of existence doesn’t make that existence meaningful. If man and the universe could exist forever, but if there were no God, their existence would still have no ultimate significance. . . . They could go on and on and still be utterly without meaning. We could still ask of life, “So what?” So it’s not just immortality man needs if life is to be ultimately significant: he needs God and immortality.

But what does God add? Craig doesn’t say. Why couldn’t we ask of eternity with God, “So what?” Craig doesn’t say. Craig’s arbitrary standards for what could constitute meaning don’t just rule out an atheist’s life having meaning to him: they rule out anything having meaning to anyone.

Purpose Without God

“Purpose,” says Craig, “has to do with a goal, a reason for something.” Here Craig’s trick is even more transparent:

If death stands with open arms at the end of life’s trail, then what is the goal of life? Is it all for nothing? Is there no reason for life? And what of the universe? Is it utterly pointless? If its destiny is a cold grave in the recesses of outer space, the answer must be, yes—it is pointless. There is no goal, no purpose for the universe. The litter of a dead universe will just go on expanding and expanding—forever.

Craig has shifted from purposes of living beings in the universe to the purpose of life and the universe absent living beings. The perspective he insists we adopt is not our own, but the perspective of someone outside of reality watching it unfold and contemplating its utility.

As I’ve argued, purposes are what living organisms have, and the ultimate purpose for any living organism is its life. What’s the purpose of life? That’s a bad question because it fails to specify: purpose to whom? For any living organism, its life is an end in itself. Life is self-sufficient: it serves no purpose outside itself. This is what it means for a purpose to be ultimate in the sense of being basic or fundamental.

It’s only if we switch the meaning of “ultimate” to “happening at the end of a process” that we run into the problems Craig is on about. What’s the purpose of your life once you’re dead? That’s not a killer gotcha question—that’s inane.

In the end, Craig is assuming what he wants to prove. His template for life’s purpose is its purpose to a supernatural creator, in which human beings are designed to serve God’s plan. Then he says: look, if you take God out of the equation, whose ends are we serving?

The rational approach is to start with the fact that living organisms very obviously have purposes and to ask what ultimate purpose rests behind those purposes. And the answer is: life.

Value With God

“Value,” says Craig, “has to do with good and evil, right and wrong.” And Craig’s charge is that, without God, you can’t establish an objective foundation for value—a foundation based on facts rather than personal taste or social convention. He even has a syllogism to prove it:

If God does not exist, objective moral values and duties do not exist.

Objective moral values and duties do exist.

Therefore, God exists.

Obviously premise 1 is doing most of the work. So why believe it? Craig offers three arguments.

Argument 1: Life is finite

The first argument is one we’ve already dealt with ad nauseam: life can have no ultimate value because you die.

If life ends at the grave, then it makes no ultimate difference whether you live as a Stalin or as a Mother Teresa. Since your destiny is ultimately unrelated to your behavior, you may as well just live as you please.

The fact that something makes no difference to you when you’re dead doesn’t erase the fact that it can make a hell of a difference to you while you’re alive. According to Craig, you should be indifferent between spending five decades in a fulfilling relationship or spending fifty years in solitary confinement because, hey, eventually you’ll end up dead.

But if fifty years of joy is not more valuable to me than fifty years of suffering, then there’s no reason why infinite years of joy should be more valuable to me than infinite years of suffering.

In reality, it makes a vital difference to you how you behave. To live and enjoy life, there are facts about human existence you have to obey. This is precisely why you need morality (see “A Morality of Reason”).

Argument 2: Valuing human life is arbitrary

And this leads to Craig’s second argument. According to Craig, the most obvious candidate for a secular ultimate value is “human flourishing.” This is different from the ultimate value I defend—your own flourishing—but Craig’s objection applies to both in very similar ways, so let’s go with it.

Craig asks, “Given atheism, why think that what is conducive to human flourishing is any more valuable than what is conducive to the flourishing of ants or mice?”

The answer to Craig’s question is obvious: it is hardly a mystery why human flourishing is more valuable to humans than the flourishing of ants or mice.

This isn’t a matter of subjective taste or preference. Values are relational facts: to be a value is to be a value to a valuer for a purpose. Any question seeking to rank how valuable something is demands that we specify which valuer is doing the ranking. It’s only by omitting any valuer that Craig can make it seem arbitrary for a human being to adopt a human perspective on values.

My flourishing is more valuable to me than the flourishing of other people, and human flourishing is more valuable to me, a human being, than the flourishing of other species. There’s nothing arbitrary or mysterious about that.

And once you adopt an individual, human perspective on values, then what is valuable is a scientific question: what promotes your well-being is not a matter of taste, convention, or emotion, but of facts (see “The Human Way of Life”).

Argument 3: Morality requires unconditional duties

According to Craig, “If there is no moral lawgiver, then there is no objective moral law that we must obey.” In A Debate on God and Morality, Craig gives an important elaboration on this point:

[H]aving decisive moral reasons to do an act implies at most that if you want to act morally, then that is an act you ought to do. In other words, the obligation to do the act is only conditional, not unconditional. But a divine command provides an unconditional obligation to perform some act. A robust moral theory ought to provide a basis for unconditional moral obligations.

Craig’s point is that a secular morality takes the form of a conditional: “You must, if.” It posits some goal you embrace by choice, and then supplies causal principles you must follow to realize that choice. The moral code I champion, for example, says, “If you choose to live, then you must follow a pro-life moral code.” (See Ayn Rand’s “Causality versus Duty.”) And Craig is insisting that a “robust moral theory” must be unconditional: you must follow morality, period.

But unconditional moral theories are incoherent. What does it mean I must obey God’s commands? It can’t mean I have no choice. Craig acknowledges human beings have free will. It can’t mean that if I disobey God I’ll go to Hell. That would make morality conditional: “If you want to avoid Hell, you must follow a religious morality.”

Craig’s worry is presumably that a conditional morality allows people to escape morality’s demands by rejecting the condition. A pro-life morality, he would say, implies that there’s nothing morally objectionable with murder or rape if the criminal doesn’t choose to live. But that doesn’t follow.

On the theory I’ve defended, your life is your ultimate value. You’re free to pursue it or not, but there is no other ultimate value to pursue and no rational moral code other than a pro-life moral code to adopt. A criminal can’t claim the sanction of morality by arbitrarily adopting murder as his goal. There is no morality of murder.

If someone does not value his own life, that doesn’t give him a “get out of morality free” card, sanctioning his desire to destroy those who want to live. “Sanctioning” is what morality does. He has chosen to make himself an enemy of life; people who do value their lives will rightly condemn him, stop him, and destroy him.

To say that morality is conditional is to say only this: if you don’t want the goal morality is designed to help you achieve, then you will not be swayed by moral reasons. This is a raw fact that no amount of handwaving about “unconditional duties” can erase. Even on Craig’s theory, if you don’t want God has to offer, you will not be cowed by His insistence that you’re violating His moral rules.

A person who rejects life and its moral demands does not need moral guidance—but he is not exempt from the consequences of rejecting morality. And the consequences for rejecting a pro-life morality are straightforward: suffering and death.

Craig’s Divine Command Theory is Non-Objective

Craig has done nothing to throw in to question the possibility of an objective secular morality. All he’s done is covertly assert that an objective morality must look like a religious morality, and then argue that you can’t have a religious morality without God and an afterlife.

But things are much worse for Craig. Because the point is not that atheists are just as capable of defining an objective morality as he is. It’s that Craig is utterly incapable of defining an objective morality.

In A Debate on God and Morality Craig summarizes his view this way:

On the theistic view objective moral values are grounded in God. As St. Anselm saw, God is by definition the greatest conceivable being and therefore perfectly good; He is the paradigm of moral value. God’s own holy and loving character supplies the absolute standard against which all things are measured. He is by nature loving, generous, faithful, kind, and so forth. Thus, if God exists, moral values are objective, being wholly independent of human beings. . . .

On the theistic view, objective moral duties are constituted by God’s will or commands. God’s moral nature is expressed in relation to us in the form of divine commandments which constitute our moral duties and obligations. Far from being arbitrary, God’s commandments must be consistent with His holy and loving nature. Our duties, then, are constituted by God’s commandments, and these in turn reflect His essential character. On this foundation we can affirm the objective rightness of love, generosity, and self-sacrifice, and condemn as objectively wrong selfishness, hatred, abuse, and oppression.

What, precisely, is Craig’s argument? At first glance, it seems to be:

God is the greatest greatest conceivable being

Therefore, God is a perfectly good being

What does perfectly good mean? Whatever God is.

Taken on its own, this theory of the good is completely empty. To give it content we have to know God’s qualities, and Craig gives us such a list: God is “loving, generous, faithful, kind.” He is characterized by “love, generosity, and self-sacrifice,” as against “selfishness, hatred, abuse, and oppression.”

But how does Craig know this?

Craig might say that we know God has these qualities because they are good, and He is perfectly good. But that only pushes the question back: how do we know these qualities are good if God “supplies the absolute standard against which all things are measured”?

Craig needs some independent way to establish what qualities are good or else his argument is circular: “We know these qualities are good because that’s what God is like; and we know that God is like this because these qualities are good.”

Though Craig is not totally clear on this point, it does appear he thinks we have independent access to God’s qualities. According to Craig, we have direct, self-evident moral knowledge, which he calls “moral experience.”

Philosophers who reflect on our moral experience see no more reason to distrust that experience than the experience of our five senses. . . . [I]n the absence of some reason to distrust my moral experience, I should accept what it tells me, namely, that some things are objectively good or evil, right or wrong.

On this account, our moral knowledge is not arrived at by reason any more than I reason my way to knowledge that I’m sitting in my office typing. But that can’t be right. Grasping that something is good is nothing like seeing, tasting, or hearing.

For starters, we can explain how sense perception works in a way that we can’t for any supposed moral sense. We can scientifically explore the nature of our eyes, ears, nervous system, light waves, sound waves, etc., and show how they interact to produce awareness. We don’t validate the senses this way: they are self-evident starting points. The point is simply that using the senses and reason, we can grasp how the senses produce awareness. Craig can do nothing remotely like this for his alleged moral sense. It’s a pure article of faith.

In reality, value judgments are conceptual judgments—they are conclusions we establish by reason, not self-evident starting points. That’s precisely why there is so much more disagreement about morality than about whether dogs exist.

It’s hard to overstate the degree of moral disagreement there has been throughout history. I don’t just mean disagreement over the application of moral principles, but disagreement about the moral principles themselves.

Take just one of the values Craig cites: self-sacrifice. The Greeks did not praise self-sacrifice but saw virtue as serving your self-interest; Aristotle went so far as praise selfishness. If moral principles really were self-evident, we should no more expect that kind of disagreement than we should expect to find physicists debating whether balls roll.

Asserting a moral sense really amounts to confessing: “I can’t prove it, but I feel that it’s true.” Such is the foundation of Craig’s supposedly “objective” moral theory.

Craig’s Dead End

Despite all his bluster, Craig never gets around to supplying us with an answer to one very important question: why, on his view, should we be moral?

But that is the basic question an objective morality has to answer.

Because even if we conceded to Craig that the good is God, and He commands us to be like Him, and even if we had some way of knowing what His commands were, at the end of the day, that still doesn’t answer the question of why we should obey His commands.

The only coherent answer is: because God will reward us if we do or punish us if we don’t.

But that answer won’t serve Craig’s purposes. First, most Christians argue that it would be wrong to follow God in order to reap personal rewards. Second, it makes morality conditional—you must be moral if you want eternal rewards rather than eternal punishments—and Craig insists that morality must be unconditional. And this points to the most important reason Craig can’t give this answer: it undermines his entire case against a secular morality of reason.

Why is that? Because it would amount to saying, “The reason you should be moral is because you have something at stake in moral action: your eternal well-being.” And that immediately grants the atheist precisely what he needs to justify a secular morality: your earthly well-being.

Once you recognize that values require stakes, then it’s trivial to show that human beings face enormous—literally life-or-death—stakes in choosing our actions on earth. And if so, then there are no grounds for Craig’s central claim that only God can give rise to objective moral values.

The only thing that makes Craig’s argument plausible is the failure of atheists to formulate a secular morality of reason. So long as atheists openly embrace moral relativism, or secularized versions of religious ethics (altruism, egalitarianism, Kantianism, utilitarianism), they cannot answer Craig effectively.

But if they uphold a morality of life? Then they can complete the case for atheism by seizing the moral as well as the metaphysical and epistemological high ground.

3 Fun Things

A Quote

“Religion means orienting one’s existence around faith, God, and a life of service—and correspondingly of downgrading or condemning four key elements: reason, nature, the self, and man. Religion cannot be equated with values or morality or even philosophy as such; it represents a specific approach to philosophic issues, including a specific code of morality.”

—Leonard Peikoff, “Religion Versus America”

A Resource

Ben Bayer & Yaron Discuss Altruism, Religion & Wokeism. Philosopher Ben Bayer reveals the immorality of altruism, its roots in religion, and how woke egalitarianism is is a product of Christian ethics. This interview has it all.

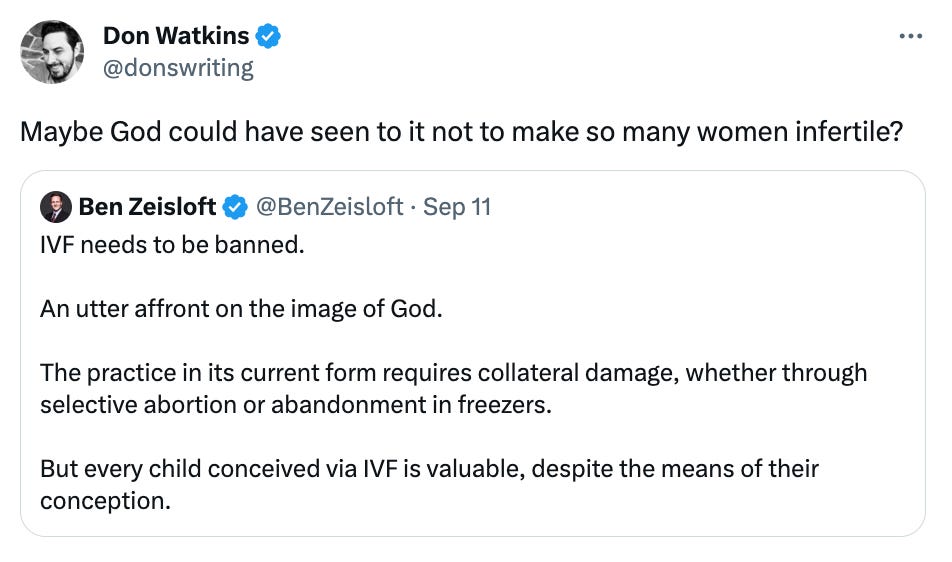

A Tweet

Effective Egoism 101

The conception of earthly idealism I champion was defined by Ayn Rand. Here are three key works that summarize her perspective:

Faith and Force: Destroyers of the Modern World by Ayn Rand

Causality vs. Duty by Ayn Rand

The Objectivist Ethics by Ayn Rand

This was probably my favorite article so far. Gigantic task to write so clearly on this subject. Kudos.

As much as Objectivists have written about selfishness and morality, this kind of essay has been desperately needed. It is an excellent easy to read deep dive into the true divide between the 2,000 year-old altruistic religious morality that pervades our world and the selfish secular morality of Ayn Rand, the first legitimate, rational human life serving morality ever presented. To a reasoning mind there is no contest. As a side note, I love the term 'Effective Egoism'. It truly presents the basic goodness of selfishness without either going over the head of your average Joe or triggering their automatic hatred of the word selfishness. Hopefully, it is a way to gain a toe-hold into a thousand year-old thoroughly entrenched evil moral code that continues to wreck our world.